See the commentary-article "Pelvic hematomas in the postpartum state" on page 354. AbstractPelvic pain and vaginal bleeding are common symptoms in postpartum women presenting to the emergency room (ER). Pelvic ultrasonography plays a crucial role in evaluating symptomatic postpartum patients by allowing a rapid diagnosis and treatment initiation. The main goal of imaging is to distinguish between causes of pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding that may be managed conservatively and those requiring emergent intervention. This pictural essay focuses on the ultrasonographic features of common postpartum conditions for which patients may present to the ER with vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain, including retained products of conception, endometritis, uterine arteriovenous malformation, uterine artery pseudoaneurysm, ovarian vein thrombosis, bladder flap hematoma, and uterine dehiscence/rupture.

The postpartum period begins immediately after the delivery of the infant and placenta and lasts for approximately 6-8 weeks, as the reproductive tract anatomically and physiologically returns to the non-pregnant state.

Pregnancy-related deaths remain a significant cause of mortality in the 21st century in the United States. The pregnancy-related mortality rate between 2011 and 2013 was 17.0 deaths per 100,000 live births. More than half of these women died in the postpartum period, most commonly due to hemorrhagic or embolic conditions [1]. Other conditions such as infection (endometritis or infection of a cesarian scar) and retained products of conception (RPOC), are also among the major causes of maternal morbidity and mortality that may require hospitalization or additional procedures [1].

Pelvic ultrasonography (transvaginal or transabdominal) is the initial imaging technique when postpartum pathology is suspected. Common indications for ultrasonography in the postpartum period include symptoms such as excessive/prolonged bleeding, severe pain, and fever. Other imaging modalities such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used for a further evaluation following the initial assessment with ultrasonography.

Pelvic ultrasonography is an adjunct to the bimanual pelvic examination for many postpartum women presenting to the emergency department with pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding. Table 1 shows the common causes of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) and pain.

PPH is described as blood loss exceeding 500 mL after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL after a cesarean section, or any amount of blood loss that results in maternal hemodynamic compromise. PPH can be divided into two groups: early (primary) PPH refers to bleeding that occurs within 24 hours after delivery, and late (secondary) PPH takes place between 24 hours and 6 to 12 weeks after delivery [2].

The most common cause of primary PPH is uterine atony, which is most often a clinical diagnosis, although ultrasonography may be utilized in order to exclude other etiologies [3]. Secondary PPH is less common than primary PPH, but can cause significant maternal morbidity and mortality [4]. Secondary PPH is frequently a sign of underlying RPOC or endometritis.

Acute pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding are two of the most common presenting symptoms of postpartum patients in the emergency room. Making the correct diagnosis may be challenging in these cases due to the lack of specific laboratory tests and sometimes equivocal physical examination findings. Therefore, imaging is usually required to aid the differential diagnosis. Ultrasonography is the primary imaging modality for assessing pelvic pathology in the postpartum period. In addition to its excellent diagnostic utility, ultrasonography is ideal because of its wide availability, portability, and lack of ionizing radiation.

Pelvic ultrasonography can be performed via a transabdominal or transvaginal approach. The transvaginal examination is performed with a high-frequency transvaginal transducer (>7 MHz). It provides excellent near-field resolution, allowing for a detailed evaluation of the endometrial cavity. The transabdominal evaluation is performed with a convex low-frequency transducer (1-5 MHz). It provides a wider field of view that can visualize free fluid or blood products outside the lower pelvis. It may also provide a better view of the ovaries in patients where the uterus remains enlarged in the early postpartum period.

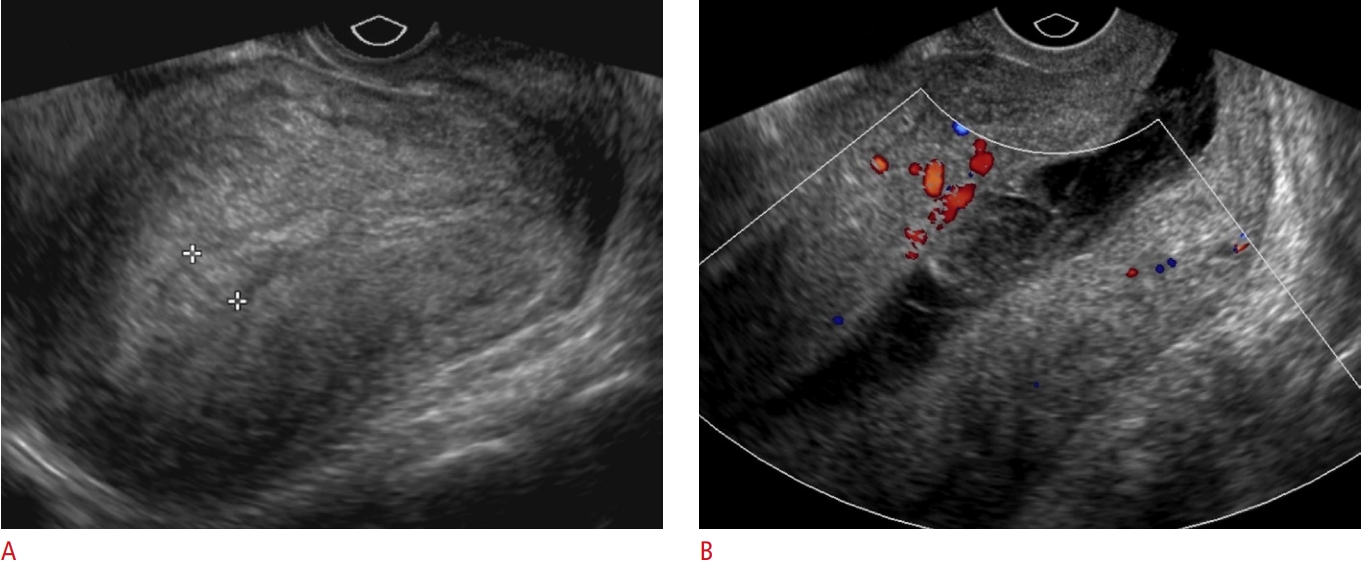

The normal postpartum uterus has a variable sonographic appearance. The endometrial cavity may contain anechoic fluid or echogenic material consistent with blood products (Fig. 1) [5,6]. These findings can be seen in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients [7]. Therefore, the clinical context is essential for interpreting the significance of these findings.

The term RPOC refers to residual fetal, placental, or other decidual tissue remaining within the uterus after delivery, miscarriage, or pregnancy termination [8]. The risk of RPOC is higher when termination occurs after the start of the second trimester.

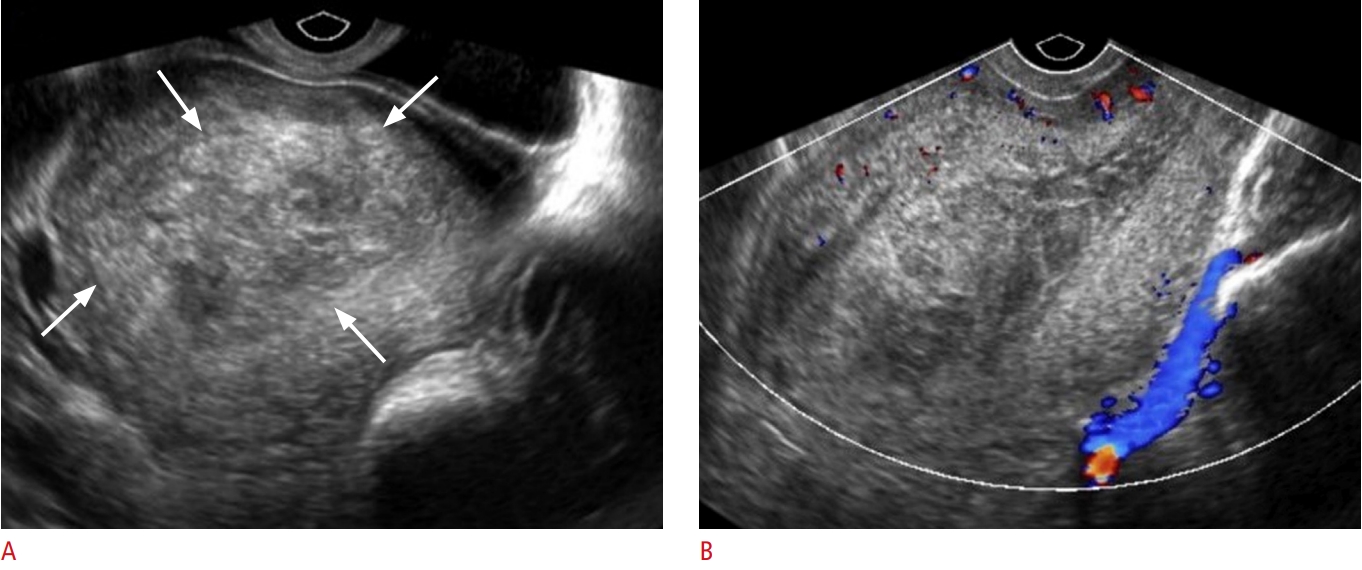

RPOC show a variable appearance on grayscale ultrasonography, ranging from a hyperechoic or mixed-echogenicity mass in the endometrial cavity to a heterogeneously thickened endometrial stripe with varying degrees of vascularity on color Doppler ultrasonography. An irregular interface between the endometrium and myometrium is another grayscale finding that has also been reported in the setting of RPOC [6,9]. If the endometrial echo-complex (EEC) is less than 10 mm without an endometrial mass, RPOC are extremely unlikely.

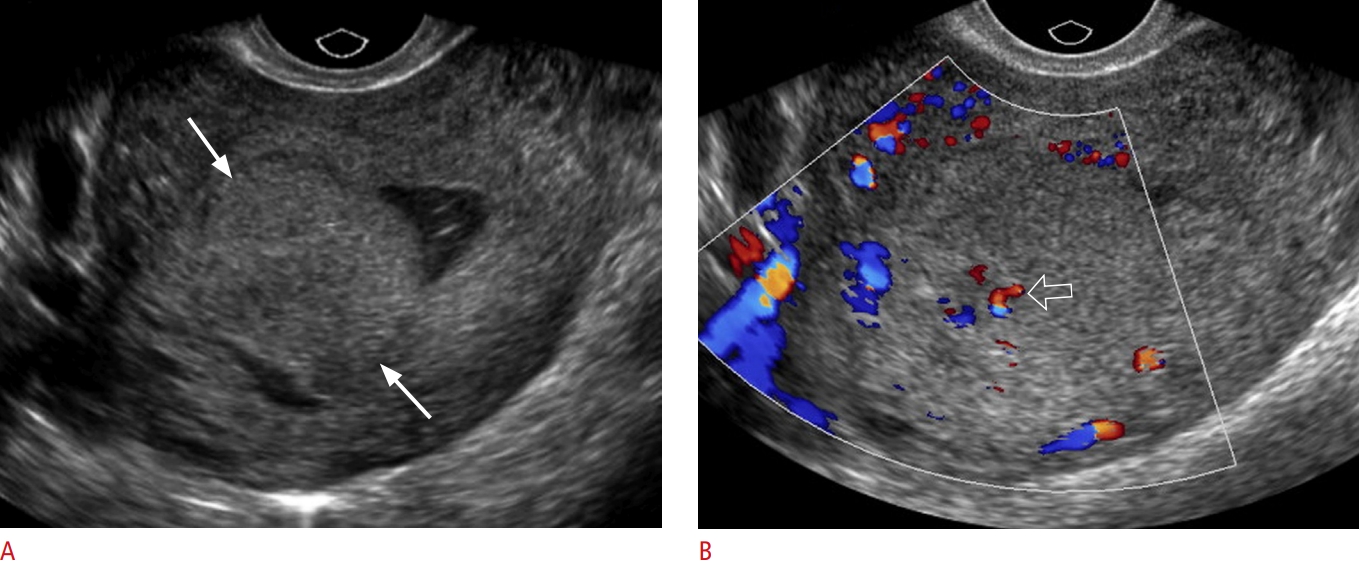

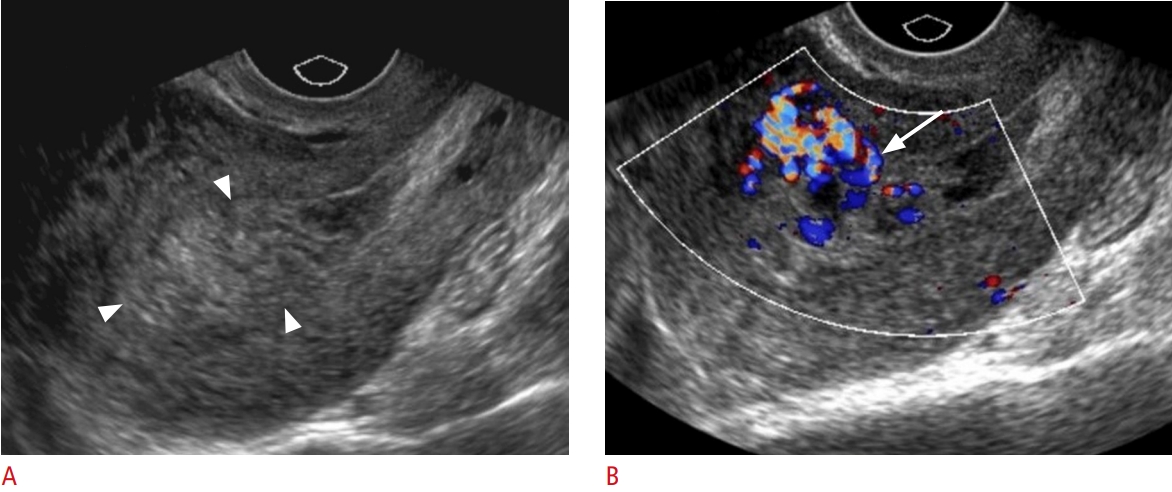

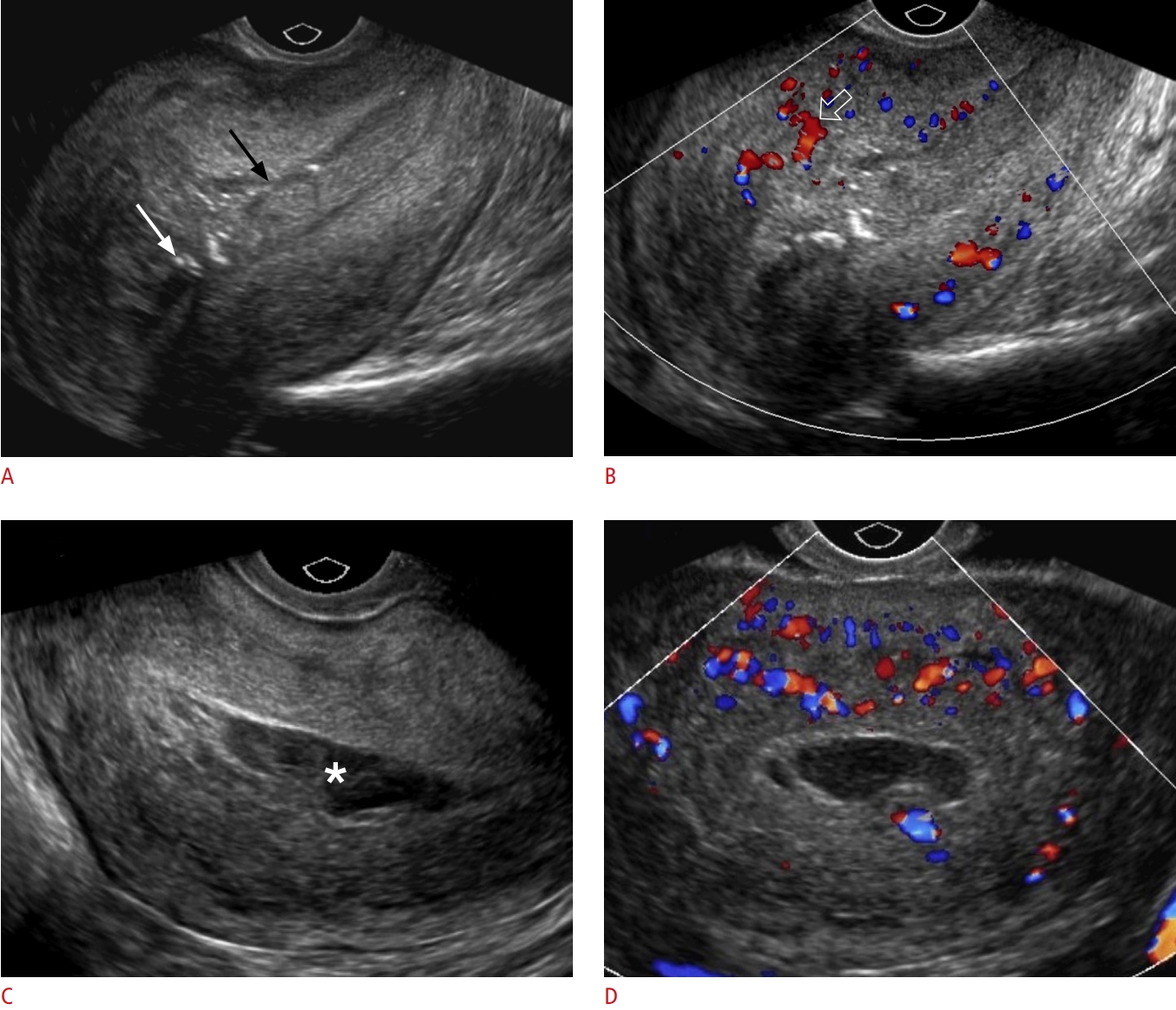

Color Doppler ultrasonography can enhance diagnostic accuracy in identifying RPOC. In patients in whom RPOC is suspected based on the clinical circumstances, the presence of vascularity in a thickened EEC or endometrial mass is highly suggestive of RPOC. The degree of vascularity can be divided into four groups by comparing endometrial vascularity to the adjacent normal myometrium (Figs. 2-6) [8,10]. Since RPOC may be avascular, the absence of color Doppler flow does not exclude the diagnosis. Avascular RPOC (type 0) and intrauterine blood clots demonstrate no flow on color Doppler ultrasonography images [10]. However, if the echogenic material within the endometrial cavity appears to be free-floating, this is more suggestive of a blood clot rather than RPOC.

When evaluating possible type 3 RPOC, it is essential to differentiate it from an arteriovenous malformation (AVM). This can be challenging, but as a general rule, the hypervascularity of type 3 RPOC will be centered in the endometrium, whereas the vascularity of uterine AVMs (UAVMs) should be centered in the myometrium [10]. UAVMs can be a life-threatening condition that requires endovascular treatment. Therefore, in cases of suspected RPOC with markedly increased vascularity, potentially either type 3 RPOC or AVM, this information should be conveyed clearly to the obstetrician to avoid dilation and curettage (D&C).

Endometritis is an infection of the endometrium and can occur after delivery or any intervention in the uterus. The risk of endometritis is greater following cesarean section than vaginal delivery [11]. The risk factors for endometritis include RPOC, prolonged labor, and premature rupture of membranes [12]. The symptoms of endometritis may include fever, pelvic pain, uterine tenderness, purulent vaginal discharge, and uterine subinvolution (prolonged postpartum enlargement of the uterus).

Endometritis is a clinical diagnosis, and its imaging findings may overlap with expected normal postpartum changes. The infected endometrium can demonstrate normal postpartum sonographic features without any specific imaging findings of infection. Fluid and echogenic debris within the endometrial cavity can be consistent with hemorrhage or clot and does not always indicate infection [6]. Alternatively, the endometrium may have a thickened and heterogeneous appearance with increased vascularity (Fig. 7). As usual, the clinical scenario will contribute greatly to the interpretation of these findings. Air within the endometrial cavity may be seen. On ultrasonography, this will manifest as echogenic foci with dirty shadowing or the ring-down artifact, which raises suspicion for infection (Fig. 7). It should be noted, however, that endometrial gas can be a normal finding for up to 3 weeks after delivery and may be seen in up to 20% of healthy postpartum patients [13]. Endometritis is treated with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics. If an infected hematoma, RPOC, or uterine abscess is detected, curettage may be required. Severe complications of untreated endometritis such as peritonitis, phlegmon, abscess, ovarian vein thrombosis, and septic thrombophlebitis occur in 1% to 4% of patients [11].

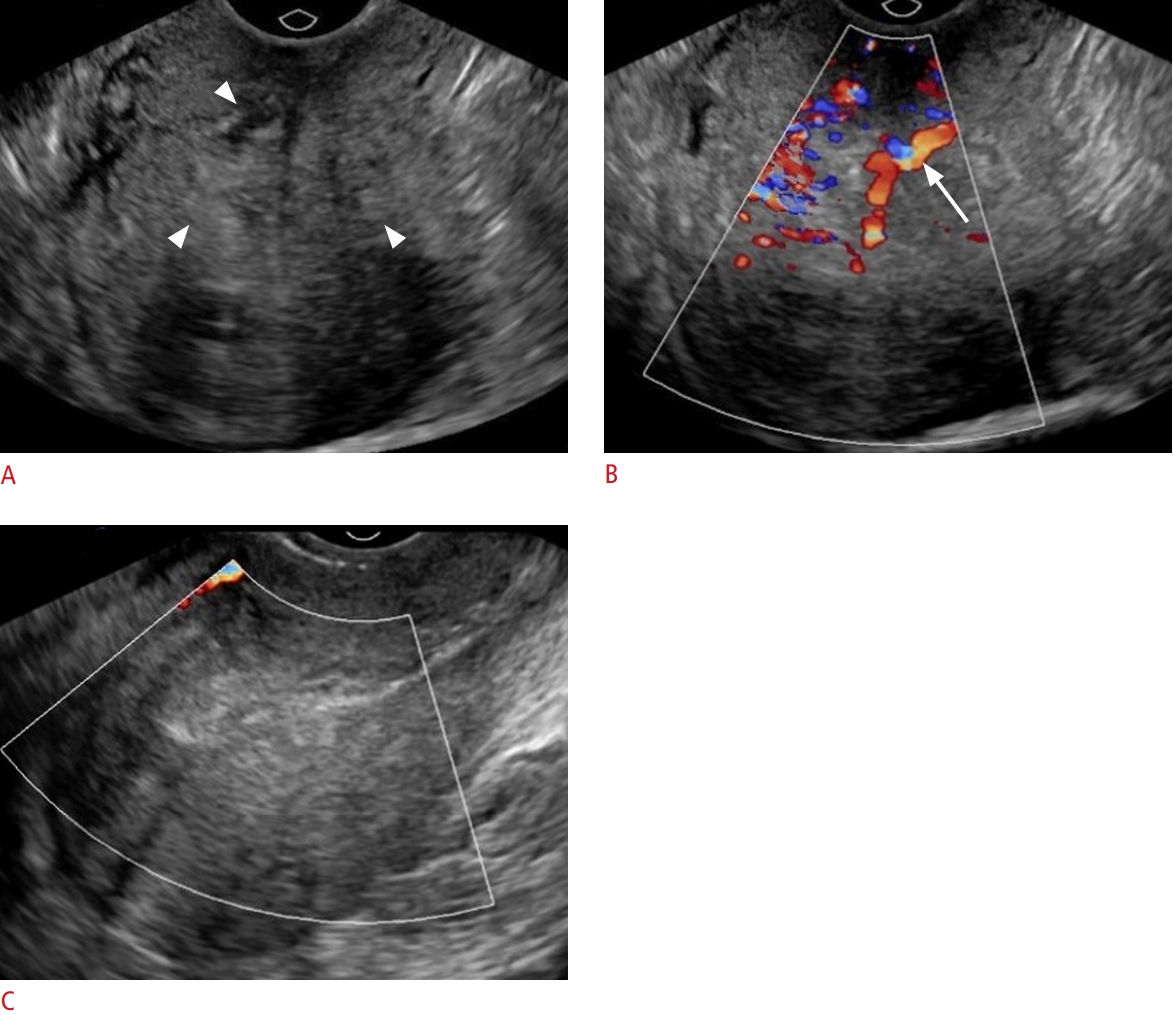

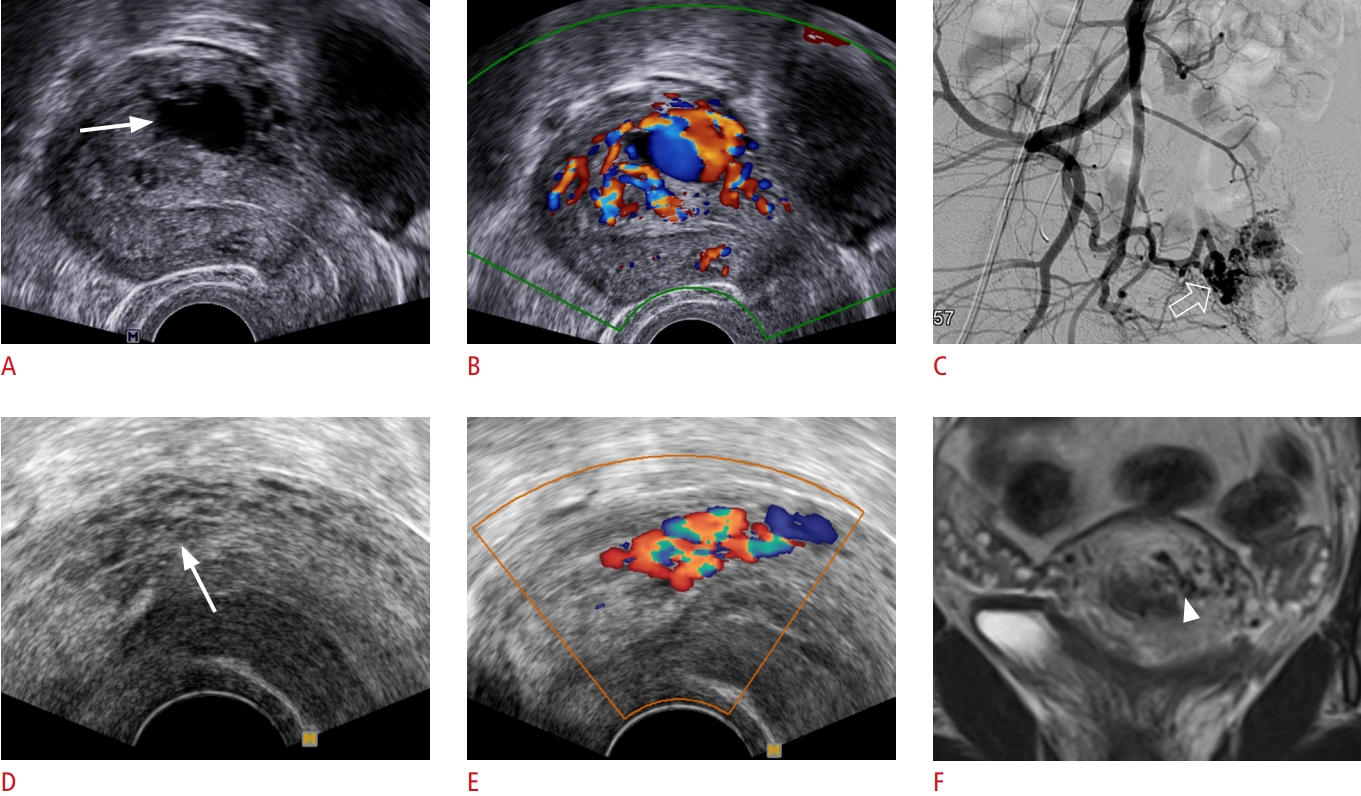

UAVMs occur when there is a direct communication between the arterial and venous systems without an intervening capillary bed [14]. UAVMs are a rare cause of postpartum bleeding and may be congenital or acquired.

Ultrasonography is the initial imaging method of choice to evaluate patients with UAVMs. Grayscale findings are often variable and non-specific, including myometrial heterogeneity or thickening. Sometimes an ill-defined heterogeneous intramural or endometrial mass may have been seen, containing multiple cystic or tubular structures (Fig. 8) [15]. Color and spectral Doppler examinations are essential to demonstrate the vascular nature of the lesion with flow in the aforementioned cystic tubular structure [14]. Doppler interrogation will show multidirectional flow with aliasing and a mosaic pattern associated with turbulent high-velocity flow [14]. If a UAVM is suspected in a patient, imaging studies should be performed prior to intrauterine instrumentation in order to exclude this diagnosis, as D&C could lead to life-threatening hemorrhage.

Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (UAP) is an abnormal outpouching of an artery that results after arterial injury [16]. Pseudoaneurysm occurs when leakage of arterial blood into surrounding tissue results in persistent communication between the artery and the contained collection of blood.

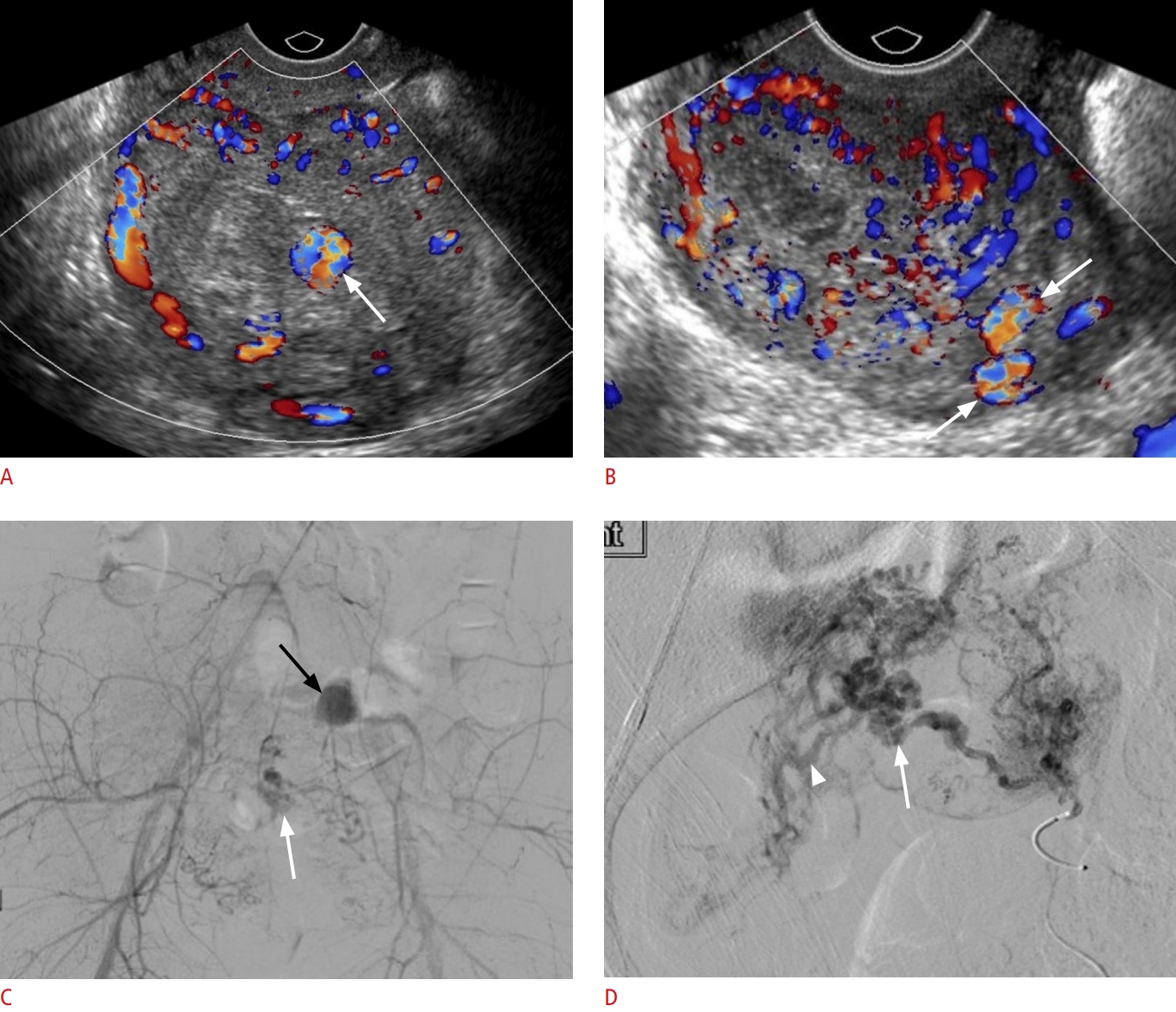

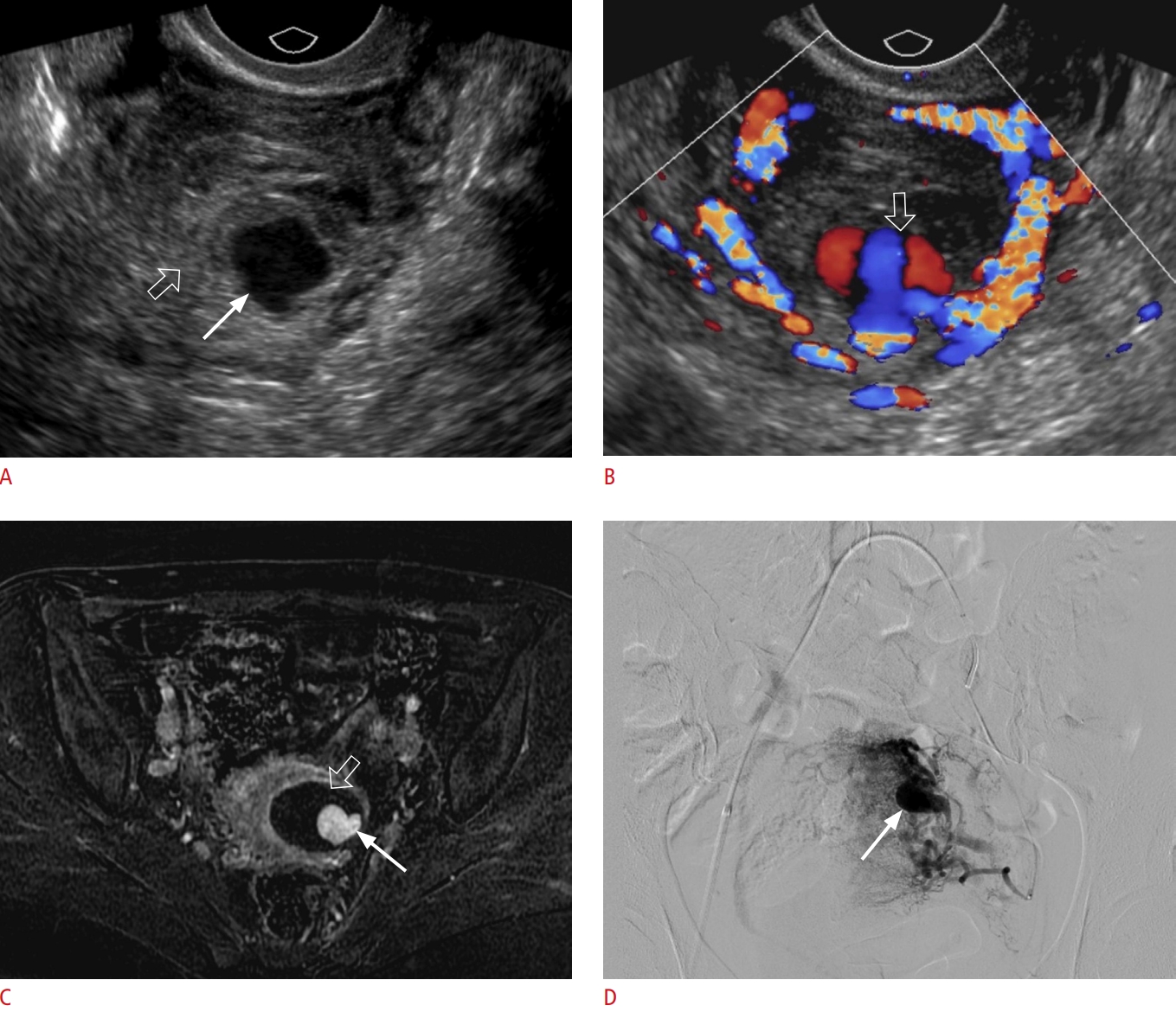

Grayscale ultrasonography images demonstrate a cystic structure within the uterus, and the color Doppler assessment should show bidirectional swirling arterial flow, which may resemble the yin-yang symbol (yin-yang sign) (Figs. 9, 10). During spectral analysis, a "to-and-fro" waveform should be seen at the neck of the pseudoaneurysm, and blood passes into and out of the pseudoaneurysm [16]. UAPs are at risk of rupture or expansion; hence an urgent intervention is required. Endovascular treatment or embolization is the first treatment choice for UAPs.

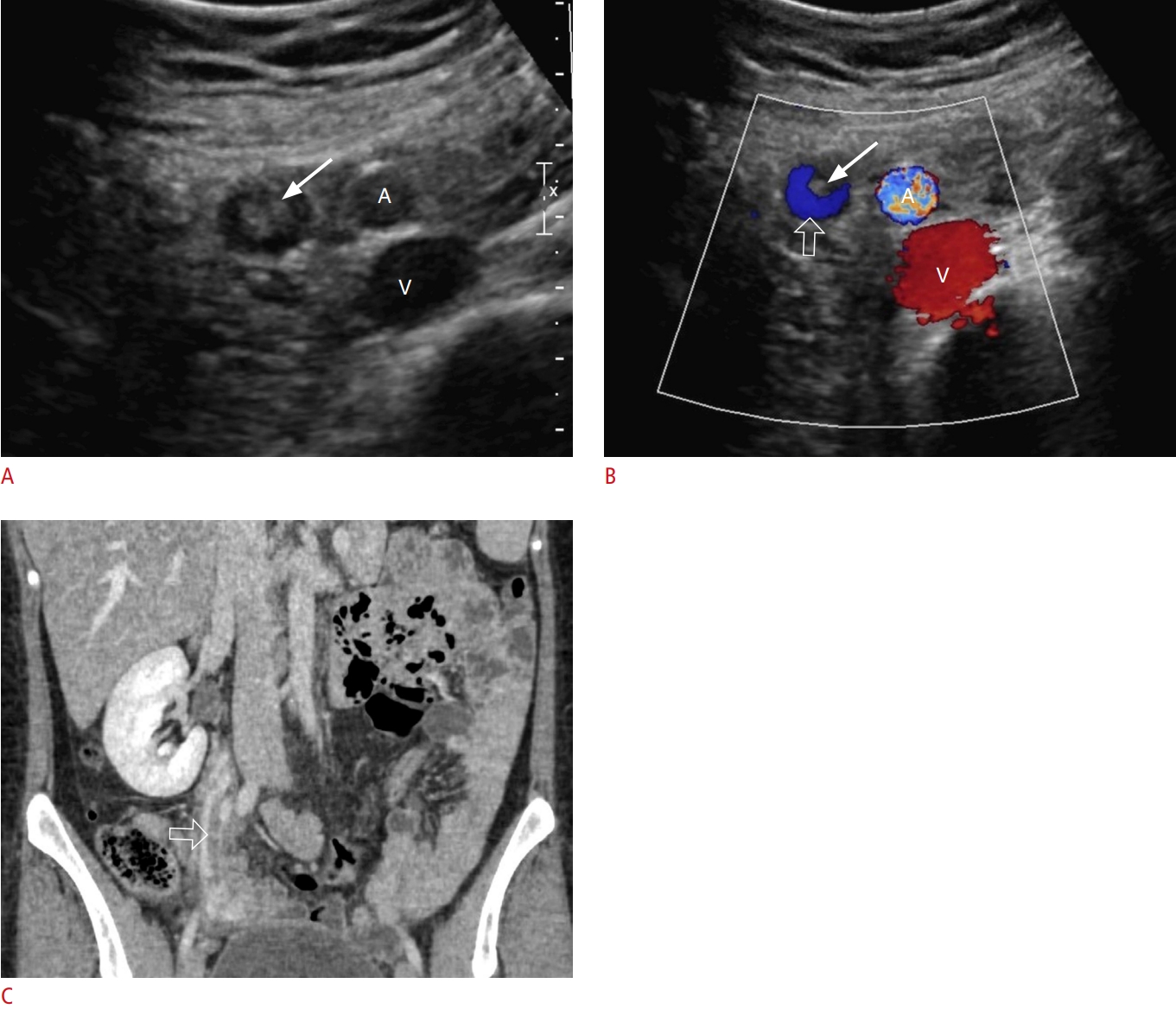

Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is a rare complication that occurs in 0.02% to 0.18% of pregnancies [17]. Most (80%-90%) cases occur in the right ovarian vein due to the usual dextrotorsion of the enlarged uterus during pregnancy, which causes compression of the right ovarian vein against the pelvic rim [17]. Patients may be asymptomatic or may complain of vague abdominal pain and fever. OVT may resolve spontaneously, but it can also lead to severe complications such as inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and sepsis. Grayscale and color Doppler ultrasonography images may demonstrate tubular or serpiginous hypoechoic structures in the adnexa adjacent to the ovarian artery without demonstrable color Doppler flow (Fig. 11) [12]. Extension of the thrombus into the IVC may be visible with ultrasonography, as well as enlargement of the ovary on the affected side.

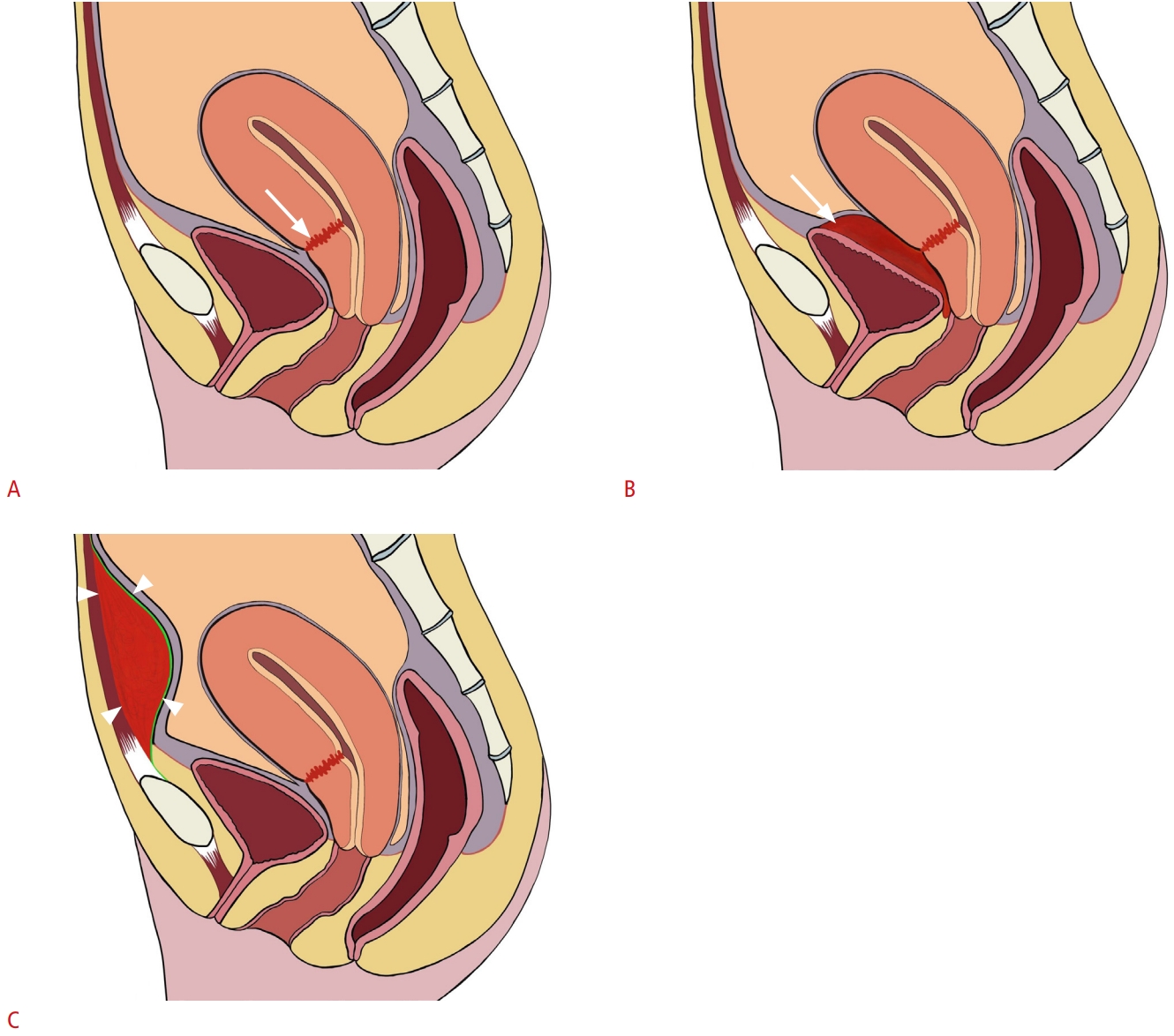

Bladder flap hematomas occur following cesarean delivery due to inadequate hemostasis and manifest as a hematoma between the bladder wall and the lower uterine segment. On ultrasound images, a bladder flap hematoma will be seen as a mixed-echogenicity avascular mass anterior to the lower segment of the uterus and posterior to the bladder wall (Fig. 12) [6]. A small bladder flap hematoma (<2 cm) is a common complication after cesarean delivery (Fig. 13). A large bladder flap hematoma (>5 cm) should alert the radiologist to the possible uterine dehiscence [18].

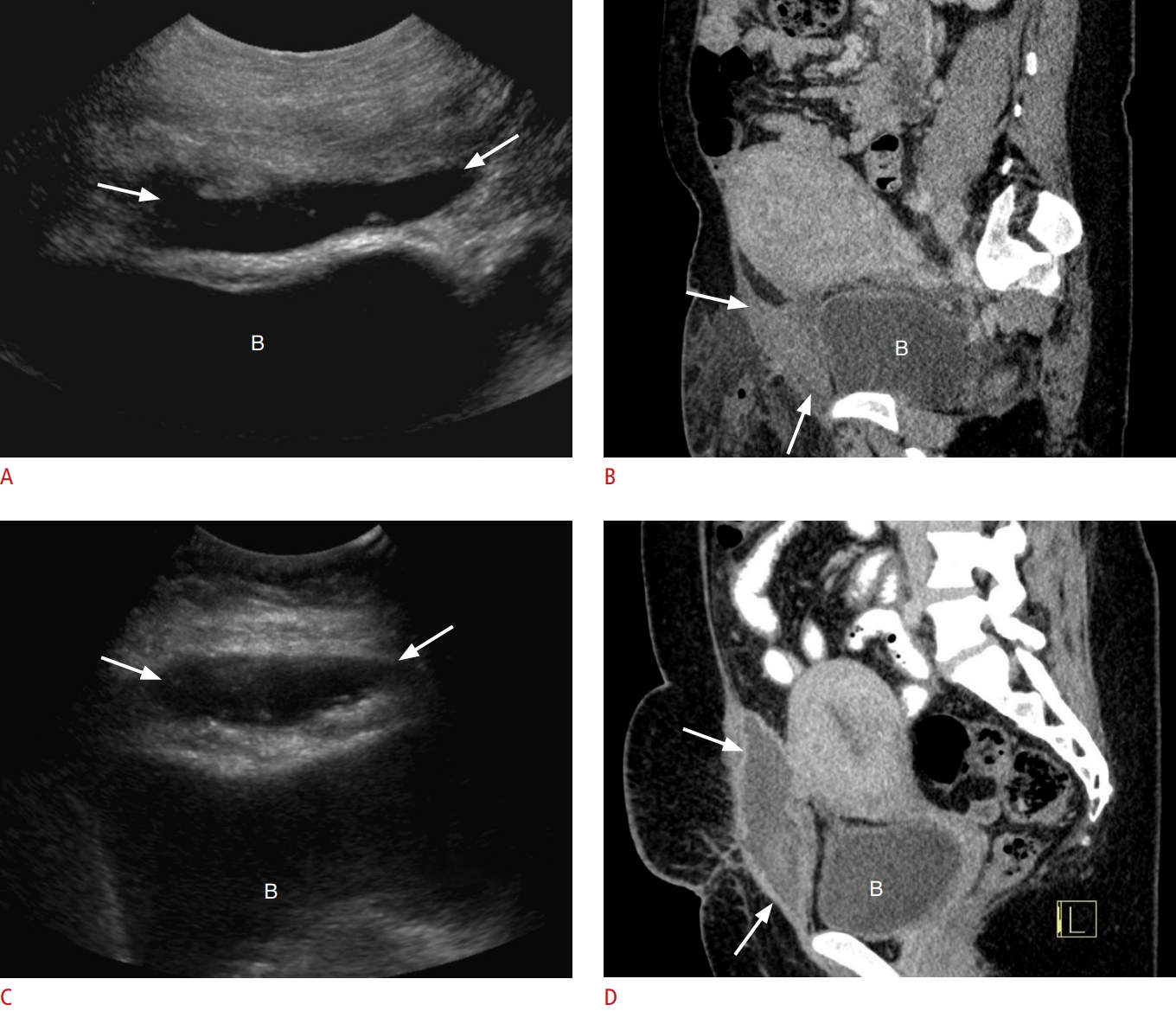

A subfascial hematoma results from injury of the epigastric vessels or their branches in the abdominal wall, and consists of a hematoma in the prevesical space, also known as the space of Retzius (Figs. 12, 14). On ultrasonography images, a cystic or complex mass will be seen deep to the rectus muscles and anterior to the bladder (Fig. 14). Significant blood loss may occur from a subfascial hematoma because the prevesical space can accommodate fluid up to a volume of 2,500 mL [19]. The presence of gas or internal septations is concerning for infected hematoma or abscess, both for subfascial and bladder flap hematomas (Fig. 14).

Uterine rupture is a rare but serious complication that usually presents with abdominal pain and may cause significant hemoperitoneum. Most uterine ruptures occur in patients with a history of previous cesarean delivery, although uterine rupture may also occur spontaneously or due to trauma. Grayscale ultrasonographic findings include a defect in the myometrium, a protruding amniotic sac (in a gravid patient), an extrauterine hematoma, a bulky empty uterus, and hemoperitoneum [20].

Uterine dehiscence (or cesarean incisional dehiscence) is characterized by a myometrial defect with an intact overlying serosal layer. The diagnosis of uterine dehiscence can be challenging due to significant overlap with the normal postoperative appearance of a cesarean delivery incision. The presence of a large bladder flap hematoma (>5 cm) has been associated with uterine rupture [18]. Contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI can be helpful to demonstrate an intact serosal layer with its robust soft tissue contrast resolution [6].

Postpartum vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain have a broad spectrum of causes, some of which may require urgent treatment. Ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice in emergency settings for assessing PPH and pelvic pain. The history and clinical findings are crucial to inform the sonographic assessment of certain conditions, such as RPOC and endometritis. As type 3 RPOC can mimic AVM, the findings should be discussed with the obstetrician for proper management. Familiarity with the clinical findings and sonographic features of conditions causing acute pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding in the postpartum period facilitates a prompt and accurate diagnosis and timely initiation of treatment.

NotesAuthor Contributions Conceptualization: Vardar Z, Dupuis CS, Goldstein AJ, Siddiqui E, Vardar BU, Kim YH. Data acquisition: Vardar Z, Dupuis CS, Goldstein AJ, Vardar BU, Kim YH. Data analysis or interpretation: Vardar Z, Dupuis CS, Goldstein AJ, Vardar BU, Kim YH. Drafting of the manuscript: Vardar Z, Dupuis CS, Goldstein AJ, Siddiqui E, Vardar BU, Kim YH. Critical revision of the manuscript: Vardar Z, Dupuis CS, Goldstein AJ, Vardar BU, Kim YH. Approval of the final version of the manuscript: all authors. References1. Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancyrelated mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:366–373.

2. World Health Organization; Maternal and Child Health Unit. The prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: report of a technical working group. Geneva. 3-6 July, 1989; Geneva: World Health Organization, 1990.

3. Knight M, Callaghan WM, Berg C, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle MH, Ford JB, et al. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:55.

4. Thonneau P, Fougeyrollas B, Ducot B, Boubilley D, Dif J, Lalande M, et al. Complications of abortion performed under local anesthesia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998;81:59–63.

5. Edwards A, Ellwood DA. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the postpartum uterus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000;16:640–643.

6. Plunk M, Lee JH, Kani K, Dighe M. Imaging of postpartum complications: a multimodality review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:W143–W154.

7. Mulic-Lutvica A, Bekuretsion M, Bakos O, Axelsson O. Ultrasonic evaluation of the uterus and uterine cavity after normal, vaginal delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001;18:491–498.

8. Sellmyer MA, Desser TS, Maturen KE, Jeffrey RB Jr, Kamaya A. Physiologic, histologic, and imaging features of retained products of conception. Radiographics 2013;33:781–796.

9. Alcazar JL, Baldonado C, Laparte C. The reliability of transvaginal ultrasonography to detect retained tissue after spontaneous firsttrimester abortion, clinically thought to be complete. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1995;6:126–129.

10. Kamaya A, Petrovitch I, Chen B, Frederick CE, Jeffrey RB. Retained products of conception: spectrum of color Doppler findings. J Ultrasound Med 2009;28:1031–1041.

11. Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD001067.

12. Cicchiello LA, Hamper UM, Scoutt LM. Ultrasound evaluation of gynecologic causes of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2011;38:85–114.

13. Wachsberg RH, Kurtz AB. Gas within the endometrial cavity at postpartum US: a normal finding after spontaneous vaginal delivery. Radiology 1992;183:431–433.

14. Mungen E, Yergok YZ, Ertekin AA, Ergur AR, Ucmakli E, Aytaclar S. Color Doppler sonographic features of uterine arteriovenous malformations: report of two cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997;10:215–219.

15. Hoffman MK, Meilstrup JW, Shackelford DP, Kaminski PF. Arteriovenous malformations of the uterus: an uncommon cause of vaginal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1997;52:736–740.

16. Kwon JH, Kim GS. Obstetric iatrogenic arterial injuries of the uterus: diagnosis with US and treatment with transcatheter arterial embolization. Radiographics 2002;22:35–46.

17. Basili G, Romano N, Bimbi M, Lorenzetti L, Pietrasanta D, Goletti O. Postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis. JSLS 2011;15:268–271.

18. Rodgers SK, Kirby CL, Smith RJ, Horrow MM. Imaging after cesarean delivery: acute and chronic complications. Radiographics 2012;32:1693–1712.

Normal postpartum uterus.A. Transvaginal grayscale ultrasonography demonstrates a normal enlarged postpartum uterus with normal endometrial echo-complex measuring 12 mm (denoted with calipers) in a 22-year-old woman on postpartum day 4. B. Transvaginal color Doppler ultrasonography of a 25-year-old postpartum patient demonstrates heterogeneous fluid within the endometrial cavity with avascular echogenic areas, consistent with blood clots.

Fig. 1.Schematic illustrations of retained products of conception with various types of vascularity (types 0-3).The degree of vascularity is measured by comparing endometrial with myometrial blood flow on color Doppler ultrasonography. Adopted from Kamaya et al. J Ultrasound Med 2009;28:1031-1041, with permission of John Wiley & Sons [10].

Fig. 2.Retained products of conception, type 0.A 36-year-old woman presented to the emergency room on postpartum day 10 with heavy vaginal bleeding, dizziness, and headache. A. Transvaginal grayscale ultrasonography of the uterus shows thickening of the endometrial echo-complex (outlined by arrows). B. Sagittalplane color Doppler ultrasonography shows no blood flow within the thickened endometrial echo-complex. The pathology was consistent with retained products of conception.

Fig. 3.Retained products of conception, type 1.A 30-year-old postpartum woman presented with vaginal bleeding and associated lower abdominal cramping for 9 days. A. Transverse grayscale ultrasonography shows an isoechoic mass (arrows) within the endometrial cavity. B. Color Doppler ultrasonography demonstrates small foci of color flow (open arrow) within the mass. The pathology was retained products of conception.

Fig. 4.Retained products of conception, type 2.A 31-year-old woman presented with persistent vaginal hemorrhage after vaginal delivery. A, B. Transverse transvaginal ultrasonography shows heterogeneous echogenic material (A, outlined by arrowheads) within the endometrial cavity with prominent vascularity on color Doppler (B, arrow). The patient was treated with dilation and curettage. The pathology was consistent with retained products of conception. C. Two-week follow-up transvaginal ultrasonography image shows complete resolution of echogenic material within the endometrial cavity. No vascularity within the endometrium is noted on color Doppler ultrasonography (C).

Fig. 5.Retained products of conception, type 3.A 39-year-old patient who had vaginal delivery 9 days ago presented with heavy vaginal bleeding. A, B. Sagittal grayscale transvaginal ultrasonography image (A) of the uterus shows a heterogeneous mass (outlined by arrowheads) expanding the endometrium. Color Doppler ultrasonography image (B) demonstrates robust vascularity (arrow) of the mass. The patient underwent dilation and curettage. The pathology was consistent with retained products of conception.

Fig. 6.Endometritis.A, B. A 34-year-old postpartum patient presented with abdominal pain, purulent vaginal discharge, fever, and leukocytosis. Longitudinal grayscale ultrasonography (A) of the uterus shows a thickened endometrium filled with heterogeneous material (black arrow) and multiple echogenic foci representing gas (arrow). A color Doppler image (B) demonstrates increased blood flow (open arrow) within the adjacent myometrium. The patient was treated with parenteral antibiotics. C, D. A 27-year-old postpartum patient with a history of premature rupture of membranes presented with lower abdominal pain, fever, vaginal discharge, and leukocytosis. Longitudinal transvaginal ultrasonography of the uterus (C) shows a distended endometrial cavity and hypoechoic fluid (asterisk) with echogenic debris. Transverse-plane color Doppler ultrasonography (D) demonstrates increased flow within the adjacent myometrium. The patient was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Fig. 7.Uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM).A-C. A 35-year-old woman presented with postpartum vaginal bleeding. A. Sagittal grayscale ultrasonography shows an anechoic cystic structure (arrow) within the myometrium. B. Corresponding color Doppler ultrasonography shows markedly increased vascularity with mosaic pattern primarily in the myometrium. C. Digital subtraction angiography demonstrates numerous arterial feeding branches (open arrow) arising predominantly from an enlarged right uterine artery, consistent with an AVM (courtesy of Dr. Sung Yoon Park, Samsung Medical Center). D-F. A 28-year-old postpartum woman presented with menorrhagia. D. Grayscale ultrasonography reveals multiple anechoic tubular structures (arrow) in the myometrium. E. Corresponding color Doppler ultrasonography shows turbulent blood flow in the anechoic structures suggestive of an AVM. F. Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the uterus shows several serpentine flow void structures (arrowhead) in the myometrium, consistent with an AVM. The patient was treated with conservative management by hormone therapy (Leuplin) (courtesy of Dr. Taek Min Kim, Seoul National University).

Fig. 8.Uterine arteriovenous fistula (AVF) and pseudoaneurysm.A 26-year-old woman who had a vaginal delivery 3 weeks ago presented with heavy vaginal bleeding. A. Transvaginal color Doppler ultrasonography shows swirling blood flow within a round structure (arrow), consistent with a pseudoaneurysm. B. A longitudinal-plane color Doppler image demonstrates serpiginous vessels (arrows) in the myometrium within the uterine body. C. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) image of the right common iliac artery shows a pseudoaneurysm (black arrow) and associated AVF (arrow) arising from a distal branch of the left uterine artery. D. Super-selective left uterine artery DSA shows the AVF (arrow) with an early draining vein (arrowhead). The patient was treated with transcatheter arterial embolization using Gelfoam and coils.

Fig. 9.Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm.A 35-year-old woman who had a vaginal delivery 4 weeks ago presents with heavy vaginal bleeding. A. On grayscale ultrasonography, a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) is seen as an anechoic round structure within the uterus with a peripheral echogenic hematoma (open arrow). B. Color Doppler ultrasonography demonstrates a typical "yin-yang" sign (open arrow) within the pseudoaneurysm that represents turbulent arterial flow. C. Axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced pelvic magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates the enhancing center of a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) and peripheral non-enhancing hematoma (open arrow). D. A digital subtraction angiographic image confirms that the pseudoaneurysm (arrow) arises from a distal branch of the left uterine artery. The distal left uterine artery was embolized using a Gelfoam slurry.

Fig. 10.Ovarian vein thrombosis.A 24-year-old postpartum woman presented with right lower abdominal pain. A. Grayscale transabdominal ultrasonography shows an echogenic thrombus (arrow) within the right ovarian vein, resulting in incomplete occlusion. B. Color Doppler ultrasonography shows echogenic thrombus (arrow) within the ovarian vein and venous flow (open arrow) in the non-occluded part of the ovarian vein. The right common iliac artery (A) and vein (V) are demonstrated in both ultrasonography images. C. Coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography demonstrates a central hypodensity (open arrow) within the right ovarian vein, which represents a partially occlusive thrombus.

Fig. 11.Schematic illustrations of a normal cesarean delivery incision, bladder flap hematoma, and subfascial hematoma.A. Normal appearance of a cesarean delivery incision (arrow) at the lower anterior uterus can be demonstrated in a normal postpartum uterus. B. A bladder flap hematoma (arrow) forms between the anterior wall of the lower uterine segment and posterior wall of the urinary bladder. C. A subfascial hematoma (arrowheads) is an extraperitoneal hematoma located in the prevesical space, posterior to the rectus muscle and anterior to the peritoneum.

Fig. 12.Bladder flap hematoma.A. A 25-year-old postpartum patient presented to the emergency room with pelvic pain. A longitudinal-plane grayscale ultrasonography image of the uterus shows a small hypoechoic collection (circle) with internal echogenicities located anterior to the uterus, which indents the urinary bladder (B). Note that the endometrial cavity is distended with a hypoechoic blood clot (arrowheads). B-D. A large bladder flap hematoma in a 26-year-old patient who had undergone cesarean delivery 5 days earlier is shown. B. Longitudinal transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrates a large heterogeneous collection (asterisk) that displaces the uterus posteriorly (arrow). C. Transverse-plane grayscale ultrasonography image shows a large hematoma (asterisk) indenting the posterior wall of the urinary bladder (B). D. Contrastenhanced sagittal computed tomography shows a hyperdense collection (asterisk) between the uterus (U) and urinary bladder (B). The patient was treated conservatively.

Fig. 13.Subfascial hematoma and abscess.A. A 22-year-old postpartum patient presented to the emergency room with lower abdominal pain. Transabdominal grayscale ultrasonography shows an anechoic fluid collection (arrows) anterior to the urinary bladder (B). B. Contrast-enhanced sagittal computed tomography (CT) image shows a high-attenuation collection (arrows) posterior to the rectus muscles and anterior to the urinary bladder (B). Note the stranding in the anterior abdominal wall from recent surgery. C, D. A 31-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with lower abdominal pain and fever 10 days after cesarean delivery. C. Transabdominal grayscale ultrasonography demonstrates a complex collection (arrows) anterior to the bladder (B). D. Contrast-enhanced sagittal CT shows a rim-enhancing collection (arrows) posterior to the rectus muscles and anterior to the bladder (B), consistent with an abscess. The patient ultimately underwent percutaneous drainage under sonographic guidance.

Fig. 14.Table 1.Common postpartum complications and symptoms |

Print

Print facebook

facebook twitter

twitter Linkedin

Linkedin google+

google+

Download Citation

Download Citation PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC