Clinical utilization of shear wave elastography in the musculoskeletal system

Article information

Abstract

Shear wave elastography (SWE) is an emerging technology that provides information about the inherent elasticity of tissues by producing an acoustic radiofrequency force impulse, sometimes called an "acoustic wind," which generates transversely-oriented shear waves that propagate through the surrounding tissue and provide biomechanical information about tissue quality. Although SWE has the potential to revolutionize bone and joint imaging, its clinical application has been hindered by technical and artifactual challenges. Many of the stumbling blocks encountered during musculoskeletal SWE imaging are readily recognizable and can be overcome, but progressive advances in technology and a better understanding of image acquisition are required before SWE can reliably be used in musculoskeletal imaging.

Introduction

Since the first sonographic images of the musculoskeletal system were obtained in 1958 [1], ultrasonography has become an important imaging modality in musculoskeletal radiology. Its inherent strengths of high spatial resolution, dynamic imaging capabilities, ability to assess vascular flow without intravenous contrast, and relatively low cost have established ultrasound as an irreplaceable modality in musculoskeletal imaging [2]. With the advent of high-frequency transducers, wide/panoramic fields of view, and improved sensitivity of Doppler imaging, ultrasound images are able to provide more detailed anatomic information about structures in the musculoskeletal system than ever before. Despite these technological advances, gray-scale and color Doppler images are unable to provide any biomechanical information about tendon quality [3]. Ultrasound elastography is an emerging technology that provides information about the inherent elasticity of tissues and has the potential to detect tissue changes induced by trauma, degeneration, healing, or tumors. Two types of elastography are currently available for clinical use in ultrasonography: strain or pressure elastography and shear wave elastography.

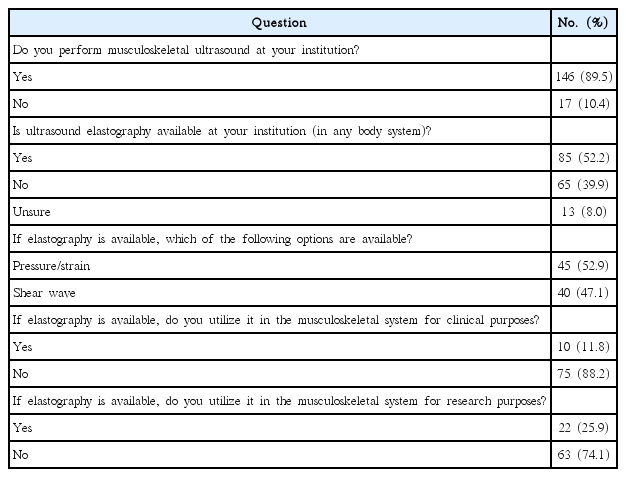

Strain elastography applies longitudinal or compressive waves to evaluate differences in tissue strain, defined as deformation of the size or shape of tissues, as a result of the stress applied. This provides qualitative data in the form of color maps and semiquantitative data by calculating the strain ratio of tissue within a region of interest (ROI) in relation to surrounding tissues. It is currently utilized in the clinical evaluation of soft tissues that are relatively homogeneous in echotexture such as the liver, breast, and thyroid. Strain elastography has not been widely adopted for routine clinical use in the musculoskeletal system in the United States, at least insofar as we were able to gauge from a recent electronic survey of musculoskeletal radiology practices (Table 1).

Responses to survey questions regarding the availability and utilization of ultrasound elastography in the musculoskeletal system

Shear wave elastography (SWE) produces an acoustic radiofrequency force impulse, sometimes called an "acoustic wind," which generates transversely-oriented shear waves that propagate through surrounding tissue (Fig. 1). The velocity of the propagating shear waves is measured (m/sec) and a qualitative color map is produced. Theoretically, the shear modulus, or tissue elasticity, can then be calculated from the shear wave speed (SWS), providing important biomechanical information about tissue quality [4]. This objective data, acquired in a novel, non-invasive ultrasound examination, provides important clinical and prognostic information and has the potential to revolutionize bone and joint imaging.

Simplified illustration of shear wave elastography demonstrating the application of an acoustic radiofrequency impulse (ARFI, arrows) and the horizontal propagation of shear waves in the tissue (horizonal waves and interrupted curved lines).

After the ARFI is applied, the transducer measures the velocity of the shear waves as they propagate through tissue, perpendicular to the original ARFI. From this information, a qualitative color map is created and a quantitative shear wave speed (SWS) is measured (m/sec). From the SWS, tissue elasticity can be calculated using the Young modulus, but it is important to consider that this calculation assumes an isotropic tissue with uniform density, and is therefore inaccurate in assessing in vivo tissues. For this reason, quantitative shear wave measurements in the musculoskeletal system are often reported as velocity or SWS, rather than tissue elasticity (kPa).

Despite the excitement around SWE, its clinical application has been hindered by technical and artifactual challenges, and the technology currently remains primarily in "research mode," with slow progress in the clinical realm over the past 15 years. The aims of this paper are to review the current state of shear wave imaging in the musculoskeletal system, to discuss the challenges related to image acquisition, to review technical obstacles, and to propose a path forward for SWE in the musculoskeletal system.

Current State of Shear Wave Elastography

Despite progress in the laboratory setting, the utilization of SWE in clinical practice is still in its infancy. An electronic survey, created via SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA; http://www.surveymonkey.com) was sent to musculoskeletal radiologists throughout the United States who were members of the Society of Skeletal Radiology. Of the 163 respondents to the survey (Table 1), 85 (52.15%) stated that ultrasound elastography (either strain or shear wave) was available at their institution. Of those, 45 respondents (52.94%) acknowledged the specific availability of SWE, a greater number than had strain elastography available (n=40, 47.10%).

Despite the fact that elastography technology was available for approximately half of the respondents, it was reported not to be widely used. In our survey, 22 respondents (25.88%) acknowledged utilization of any form of elastography for research purposes, while only 10 (11.76%) reported utilizing any form of elastography for clinical purposes. When queried about specific utilization of SWE, only five respondents (5.88%) stated that they utilized SWE in a clinical setting, and all five of those respondents worked in academic settings.

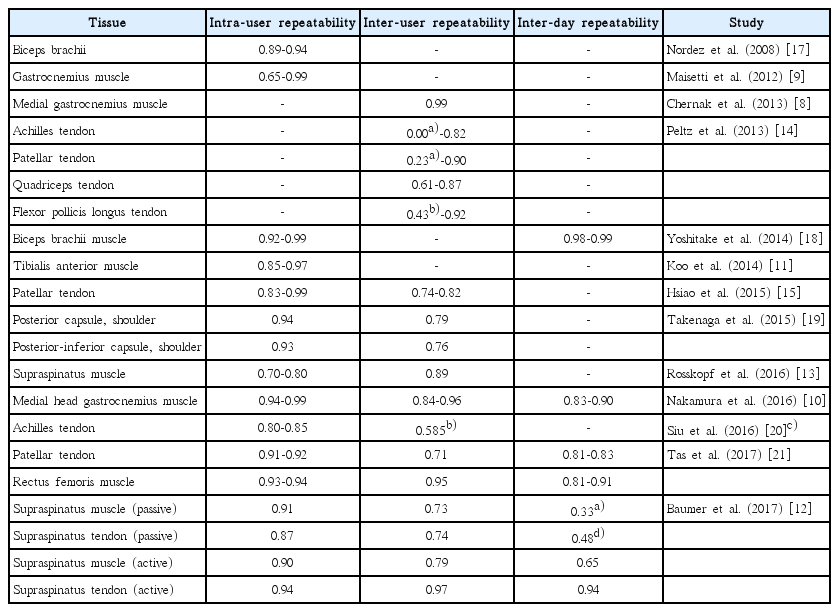

The reasons for the delayed clinical implementation of SWE in the musculoskeletal system are multifactorial but relate, at least in part, to difficulty obtaining reliable SWS measurements. While previous studies have demonstrated excellent inter-reader repeatability in the skin [5], and almost perfect inter-reader repeatability in the breast [6] and liver [7], results in the musculoskeletal system have been much more varied. Intra-user repeatability has been reported as good to very good (intra-class correlation coefficient [ICC] >0.6) in the majority of studies on both tendons and muscles. There are, however, still many discrepancies in inter-user repeatability (Table 2). While inter-user repeatability was reported to be good to very good (ICC >0.6) for the gastrocnemius [8-10], tibialis anterior [11], and supraspinatus [12,13] muscles and for the flexor pollicis longus [14], quadriceps [14], patellar [15], and intramuscular supraspinatus [12] tendons, it was only reported as fair to moderate (0.2<ICC<0.6) for the abdominal wall muscles [16] and the Achilles [14] and patellar tendons [14].

Reported intra-user, inter-user, and inter-day repeatability for shear wave measurements organized by author, the tissue being analyzed, and repeatability values

Despite a fairly substantial body of work supporting inter-user and intra-user repeatability across a wide range of musculoskeletal tissues, the reliability of day-to-day measurements is less well studied and remains poorly understood (Table 2). Some studies have shown that, even with good or very good intra-reader and inter-reader repeatability, inter-day repeatability may be poor [12]. Only a few studies have shown good to very good inter-day repeatability (ICC >0.6) for the medial gastrocnemius [10], rectus femoris [21], and supraspinatus [12] muscles and the patellar [21] and intramuscular supraspinatus [12] tendons.

As an emerging technology, there is significant variation in the study design, study implementation, and, not surprisingly, published results of SWE research. Additionally, SWE measurements made using standardized ultrasound phantoms with standardized methods demonstrated statistically significant differences in SWS estimations among systems and depending on the depth of the object [3]. Given these inconsistencies, it is not surprising that SWE has not made any permanent inroads into mainstream musculoskeletal imaging.

Challenges Inherent to Musculoskeletal Tissue

Musculoskeletal Tissue Heterogeneity

The background tissues in body systems where SWE is widely used and accepted, such as the liver, skin, and breast, are relatively homogeneous when compared to tissues in the musculoskeletal system. One possible explanation for discrepancies in SWE measurements in the musculoskeletal system is the inherent heterogeneity of musculoskeletal tissues. Individual skeletal muscle fibers are surrounded by endomysium, organized into fascicles that are surrounded by perimysium, and grouped into a muscle belly that is surrounded by epimysium. Nerve, arteries, veins, and lymphatic vessels course between muscle fascicles throughout the muscle. This intramuscular vasculature has been shown to affect SWE measurements, with higher measured SWS values around vessels than in other areas of the medial head gastrocnemius muscle; the vasculature also alters color maps, with more variation in color maps when vessels are included in the field of view [22]. These findings are exacerbated on short-axis imaging, as vessels are more difficult to visualize and may be inadvertently included in the field of view.

Traditionally in musculoskeletal imaging, long-axis and shortaxis images are obtained in relation to the structures being imaged. Depending on the specific muscle of interest, the individual muscle fibers may be parallel or obliquely oriented in relation to the long axis of the muscle. In pennate muscles, an aponeurosis runs along the superficial margins of the muscle, attaching the muscle to the tendon. If all muscle fascicles are on the same side of the tendon, the muscle is classified as a unipennate muscle. If, however, there is a single central tendon with muscle fascicles on both sides of the tendon tissue, the muscle is classified as bipennate, and if there are multiple central tendons with multidirectional muscle fibers, it is classified as multipennate. Given these variations in muscle architecture, the orientation of the transducer while positioned for long-axis imaging of the muscle belly may result in "off-axis" or oblique imaging of individual muscle fibers, a factor that may affect shear wave measurements.

Background Tissue Activity

Although not widely studied, the underlying state of the muscle or tendon may affect SWS measurements. While the stiffness of muscles increases during contraction, probably due to increased cross-bridge formation [18], underlying edema or inflammation may also affect SWS measurements. Most SWE studies have been performed on passive muscles and tendons, but some studies have focused on changes in SWS measurements with muscle activation and have demonstrated a linear relationship between increasing SWS measurements and progressive isometric contraction of the biceps brachii, suggesting that SWE is a feasible modality for quantifying muscle stiffness [17,18,23].

While differences in SWS measurements have been observed between active and passive muscles, the exact relationship remains unclear [8,24]. Interestingly, a study by Baumer et al. [24] measured SWS in the supraspinatus tendon and muscle at rest (passive) and with minimal muscle activation (slight abduction of the arm). They found that the active SWS measurements were greater than the passive SWS measurements in both the muscle and tendon, in agreement with previously published studies. In addition, while both passive and active repeatability measurements on a single day were very good, there was only fair repeatability in passive tissue from day to day. In contrast, active tissue displayed much greater day-to-day repeatability. While the reasons for the variations in passive tissue SWS measurements are not fully understood, it is possible that passive tissue may be more sensitive to changes in mechanical loading associated with activities of daily living; standardizing this from day to day may not be feasible and may account for the day-to-day variations in measurements. It is possible that mild activation of the muscle and tendon helps standardize the tissue state, resulting in improved day-to-day repeatability, which could possibly increase the accuracy of longitudinal studies.

Tissue Depth and Overlying Soft Tissues

Several studies have investigated the effect of tissue depth on SWS measurements. An in vivo study [25] demonstrated that the average SWS in the vastus lateralis muscle did not change with imaging depth within the muscle, although the variance within the ROI increased as depth increased. Another study by Dillman et al. [26] revealed that phantoms with SWS measured between 0.5 and 3 m/sec showed little change in SWS measurements with changes in depth.

To illustrate and expand upon these findings, we created a "soft" (5% gelatin) and a "stiff" (10% gelatin) phantom using water, unflavored gelatin, and psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid fiber, as detailed by Bude and Adler [27]. The phantoms were then imaged, with the deepest aspect of the ROI box positioned from 3 to 6 cm, at 1 cm increments (Fig. 2A-D). The average SWS measured in the "soft" phantoms was 1.90 m/sec, a SWS that has been observed in passive muscle [10,12,13]. The average SWS measured in the "stiff" phantoms was 3.97 m/sec, a SWS that has been observed in active muscle or smaller tendons [12].

Multiple shear wave elastography color maps of a soft phantom, whose shear wave speed (SWS) was consistent with passive muscle (average SWS 1.90 m/sec, 5% gelatin), with the region of interest (ROI) box centered at depths of 2 cm (A), 3 cm (B), 4 cm (C), and 5 cm (D).

There is relatively uniform color in the superficial ROI (A, B), with a slight, progressive increase in color variability in the deeper ROI (C, D). To confirm that the variability was related to depth and not inherent to the phantom, the phantom was flipped 180° and an additional color map was obtained (E), which demonstrated uniform color.

The soft phantom showed little change in SWS with increasing depth, although some variability in color was seen in the deeper ROI images. To confirm that this slight change in variability was related to depth of ROI and not settling of components of the phantom during preparation, the phantom was flipped 180° (Fig. 2E) and reimaged. The results when the ROI was positioned over the same physical area, but closer to the transducer, demonstrated that the measurement errors in the phantom were indeed a function of depth and not a feature of phantom inhomogeneity.

The stiff phantom showed similar color maps with superficial positioning of the ROI (Fig. 2A, B), but variation in color was apparent when the ROI was positioned at 5 cm (Fig. 3C) and the SWS field changed almost completely at 6 cm (Fig. 3D). Again, to confirm that these changes were related to depth, and not settling of components of the phantom during preparation, the phantom was flipped 180° (Fig. 3E) and reimaged. The ROI positioned over the same physical area, but closer to the transducer, demonstrated that the measurements in the phantom were indeed a function of depth and not a feature of phantom inhomogeneity.

Multiple shear wave elastography color maps of a hard phantom, whose shear wave speed (SWS) was consistent with active muscle, (average SWS 3.97 m/sec, 10% gelatin), with the region of interest (ROI) box centered at depths of 2 cm (A), 3 cm (B), 4 cm (C), and 5 cm (D).

The images demonstrate color variability at the deepest margins of the ROI, starting at a depth of approximately 4 cm (B), which progressively worsened with deeper positioning of the ROI (C, D). To confirm that the variability was related to depth and not inherent to the phantom, the phantom was flipped 180° and an additional color map was obtained (E), which demonstrated uniform color.

From these studies we can conclude that, in a phantom whose SWS was consistent with passive muscle, there was little to no effect of increasing depth on SWS measurements. A cadaveric study by Hatta et al. [28], in which the SWS of the supraspinatus was measured as overlying tissues were sequentially removed, also revealed no influence of overlying tissues on SWS measurements, further supporting the lack of influence on passive tissues. In a phantom whose SWS is consistent with active muscles or medium-sized tendons, however, artifactual changes in the SWS field begin at depths of ~4 cm; thus, although the depth of a passive muscle may not affect SWS, the influence of stiffer superficial layers is not yet fully understood.

Underlying Osseous Structures

In addition to the heterogeneity of musculoskeletal tissues, the tissues being imaged often directly overlie osseous structures, introducing an additional challenge to the acquisition of SWS measurements. While this seems to be a persistent obstacle in the musculoskeletal system and cannot be completely eliminated, the interference of underlying bones can be decreased by modifying the position of the patient and transducer.

Reflection artifacts are most easily identified when tissues are in a passive state. Long-axis B-mode imaging of the insertional supraspinatus tendon, as seen in Fig. 4A, and the corresponding color map, as seen in Fig. 4B, reveal inhomogeneity in SWS measurements within the supraspinatus tendon and overlying deltoid muscle, with low SWS (blue) and high SWS (red) measurements present in the same muscle and tendon. While it is possible that inhomogeneity such as this could be real, the linear alignment of these changes suggests that it represents a reflection artifact. This observation is based upon the fact that the image was obtained with the subject in the Crass position (shoulder internally rotated and slightly extended, elbow flexed 90°, forearm pronated and positioned behind the back). In this position, the deltoid is in a resting state and, barring substantial muscular pathology, is expected to exhibit relatively uniform SWS. Furthermore, the red and green colored areas are seen in the areas directly above prominent convex bony features, an area that we have termed the "reflective corridor" (Fig. 4C, corridor outlined in interrupted red lines). In this case, the displacement field generated by the SWE is substantially disrupted, such that even in areas between the main reflective corridors, the accuracy of the measurements may be unreliable.

Long-axis B-mode imaging of the insertional supraspinatus tendon and the corresponding color maps of shear wave elastography.

Gray-scale sonographic image of the insertional supraspinatus tendon (A), demonstrating the overlying deltoid muscle and the bony acoustic landmark of the underlying greater tuberosity with the patient in the typical Crass position (far internal shoulder rotation, flexed elbow, pronated forearm) and the transducer oriented along the long axis of the tendon. Color maps produced during shear wave elastography imaging of the same region (B, C) demonstrate some vertical, linear bands of signal abnormality in the supraspinatus tendon and deltoid muscle, extending to the superficial soft tissues which are contained within dashed parallel lines in C. While these changes could represent inhomogeneity of tendon/muscle, the linear pattern of signal change and the focal osseous convex margins deep to these areas, depicted by red circles in C, suggest that the signal changes were artifactual, representing a "reflective corridor."

Fortunately, this reflection artifact can be minimized. In our experience, convex surfaces generate the most substantial interruptions to the displacement field, while concave surfaces tend to generate more localized disruptions, although this has not yet been fully evaluated. While it may be impossible to eliminate reflection entirely, depending on the tissue being observed, it may be possible to shift the reflection corridor to a less important area within the field of view. For example, in Fig. 5, the transducer orientation was changed slightly to view the supraspinatus tendon insertion site in a non-traditional, slightly oblique orientation. With this slight change in the transducer position, the underlying bony backdrop was minimized, as the convex superficial bony margins were shifted to the periphery of the field of view. The images in Fig. 5 are from the same subject as above and nicely illustrate how the corresponding SWE image is much more homogeneous in both the supraspinatus tendon and overlying deltoid muscle. Often, as in this case, the convex bony features are not entirely avoidable, but can be shifted to the lateral margins of the ROI, creating usable, reliable data within the area between the reflective corridors.

Oblique-axis B-mode imaging of the insertional supraspinatus tendon and the corresponding color maps of shear wave elastography.

Gray-scale sonographic image of the insertional supraspinatus tendon (A), the overlying deltoid muscle, and the bony acoustic landmark of the underlying greater tuberosity with the patient in the typical Crass position (far internal shoulder rotation, flexed elbow, pronated forearm), but with the transducer orientation slightly oblique to the long axis of tendon. Color maps produced during shear wave elastography imaging of the same region (B, C) again demonstrate some vertical, linear areas of inhomogeneity, contained within dashed parallel lines in C, located superficial to focal osseous convex margins, depicted by red circles in C. When compared to the images in Fig. 4, the signal changes in these images are much less pronounced and the "reflective corridors" are shifted to the lateral margins of the field of view, minimizing their effect on shear wave speed measurements.

Admittedly, even these optimized images demonstrate inhomogeneity, as shown by the presence of some subtle streaks inside the tendon that may be artifactual and related to reflection; however, smaller reflections like these may be eliminated as machine settings and imaging algorithms continue to advance.

Potential Pitfalls and Technical Considerations

Transducer Positioning

The position of the ultrasound transducer is a modifiable variable that should be considered when performing SWE. Shear waves propagate more readily along muscle fibers when the transducer is oriented longitudinally, rather than perpendicular or at a 45° oblique angle [29,30] to the tendon, and SWE measurements obtained parallel to the muscle fibers increase, as expected, with increasing tensile load [29].

Chino et al. [22] obtained transverse and longitudinal shear wave measurements of the biceps brachii, a unipennate muscle, and the medial head gastrocnemius, a bipennate muscle. The results from these studies demonstrated more similar measurements in the transverse and longitudinal planes when scanning the medial head gastrocnemius and more variable measurements when scanning the biceps brachii. The differences in measurements were likely related to the underlying muscle fiber orientation, as shear waves propagate more quickly along the parallel (unipennate) muscle fibers of the biceps brachii, resulting in high SWS when imaged in the longitudinal plane and a significantly lower SWS when imaged in the transverse plane. Conversely, the muscle fibers of the medial head gastrocnemius are oriented oblique to the central tendon, and are therefore obliquely oriented in both the traditional longitudinal and transverse imaging planes. Consequently, the medial head gastrocnemius SWS measurements were more similar in the longitudinal and transverse planes.

The importance of longitudinal probe positioning has since been confirmed for the medial gastrocnemius, rectus femoris, biceps brachii, and rectus abdominus muscles, where images obtained with the transducer positioned transverse (or perpendicular) to the long axis of the muscle demonstrated lower image stability (i.e., increased color distribution throughout the image) than those obtained with the transducer positioned longitudinal (or parallel) to the long axis of the muscle [22].

Transducer Pressure

During traditional ultrasound scanning, the transducer applies firm, consistent pressure to the skin surface. When working with SWE, however, transducer pressure should be avoided or standardized as applied pressure compresses tissues below the surface. Tissue compression increases SWS measurements in all tissues, but the effect is particularly important in soft tissues where an increase in compression of ~10% doubles SWS measurements [31]. In order to standardize measurements and avoid this induced variability in SWS measurement, consistent, light transducer pressure or a mounted transducer should be used during SWE imaging.

Patient Positioning

A good understanding of the functional musculoskeletal unit being imaged is important in SWE of the musculoskeletal system, specifically related to the strain behavior of soft tissues relative to joint position. Several studies have correlated increased tension in the tissue with increased SWS measurements [23,32-35]. In a cadaveric study, a large increase in strain over a small range of flexion was observed in the patellar tendon. Specifically, when flexion minimally increased from 20° to 30°, strain disproportionately increased from ~2% to ~6%. The same study also documented fairly static strain in the patellar tendon from 30° to 50° flexion, which is an important detail to remember when studying this tendon [36].

As SWS measurements vary with changes in tissue state, and alterations in joint position result in changes in tissue state, it is likely that SWS changes are affected by joint position, although this information has not been integrated into clinical imaging, to our knowledge. A more rigorous study of the interactions among tissue strain, joint position, and SWS measurements is necessary to draw a firm conclusion, but the current evidence suggests that joint positions that display rapid strain changes are not ideal positions for SWE imaging.

Decreasing Motion

One of the primary artefacts that may appear in SWE relates to movement. This motion artifact can either be due to movement of the probe relative to the subject (user-induced) or movement of the tissue relative to the probe (subject-induced). Motions that can influence SWS readings can be as subtle as a muscle twitch during the acquisition sequence. Regardless of the origin, motion has an impact on the quantitative results obtained during SWE imaging.

To demonstrate the effect of a small movement on the SWS field calculations, a simple study using a "soft" gelatin phantom (5% gelatin) was performed. In the first condition, both the phantom and the ultrasound probe were fixed in place and several SWE images were acquired (Fig. 6). In these trials, the phantom appeared to be fairly uniform, with an average SWS of 3.97 m/sec and an average intra-image variance (standard deviation/mean) of 0.42 m/sec. In the second condition, the probe was held fixed in place, but a small amount of motion was induced in the gelatin by generating a small-magnitude translation at the end furthest from the probe (Fig. 7). In this case, the SWS field demonstrated areas of high and low SWS where none had been observed before the induced motion. This motion altered SWS substantially, with the average SWS dropping to 3.32 m/sec and the intra-image variance more than doubling to 0.86 m/sec.

Diagram illustrating an ultrasound probe that was fixed in place, a gel phantom that was also fixed in place (outlined by a rectangle) and the resultant shear wave elastography color map.

In this case, the shear wave elastography color map is fairly uniform, with an average variance of 0.42 m/sec and a measured shear wave speed of 3.97 m/sec.

Diagram illustrating an ultrasound probe that was fixed in place, with the same gel phantom as in Fig. 6, with induced motion indicated by horizontal arrows, and the resultant shear wave elastography color map of the same phantom.

In this case, the shear wave elastography color map demonstrates nonuniformity, with the variance more than doubling to 0.86 m/sec and the shear wave speed dropping to 3.32 m/sec.

The characteristics observed in this simple study have also been observed during in vivo trials from motions as simple as a deep breath or a palpable muscle spasm. It is important to realize the possibility of this artifact and to control for it as best as possible. Multiple images taken with the participant and user both aiming to remain still will help eliminate motion artifacts. Furthermore, repeated imaging will help identify any trials where an involuntary motion did occur, as shown either by an image appearing different from the other trials or by the SWS being different. As in other imaging modalities, it may be good practice to ask participants to inhale and hold their breath for the duration of each image acquisition.

Data Analysis and Reporting Suggestions

"Shear Wave Speed" versus "Tissue Elasticity"

The calculation of tissue elasticity is based upon the assumptions that the soft tissues are elastic, incompressible, homogeneous, and isotropic [3]. The SWS measured during SWE is only a portion of the calculation of the Young modulus, which is needed to determine tissue elasticity, as E=3μ=3pcT2, where E=the Young modulus, μ=the shear modulus, p=tissue density, and cT=the speed of transversely propagated waves, or shear waves [37]. With this relationship, unless the tissue density is 1 g/mm3, the SWS does not correspond exactly with the Young modulus [3]. The musculoskeletal system, with its viscoelastic, heterogeneous, anisotropic tissues, presents inherent challenges to calculating tissue elasticity using the Young modulus. As a result, SWE measurements in the musculoskeletal system should be presented in terms of SWS (m/sec), rather than tissue elasticity (kPa).

Conclusion

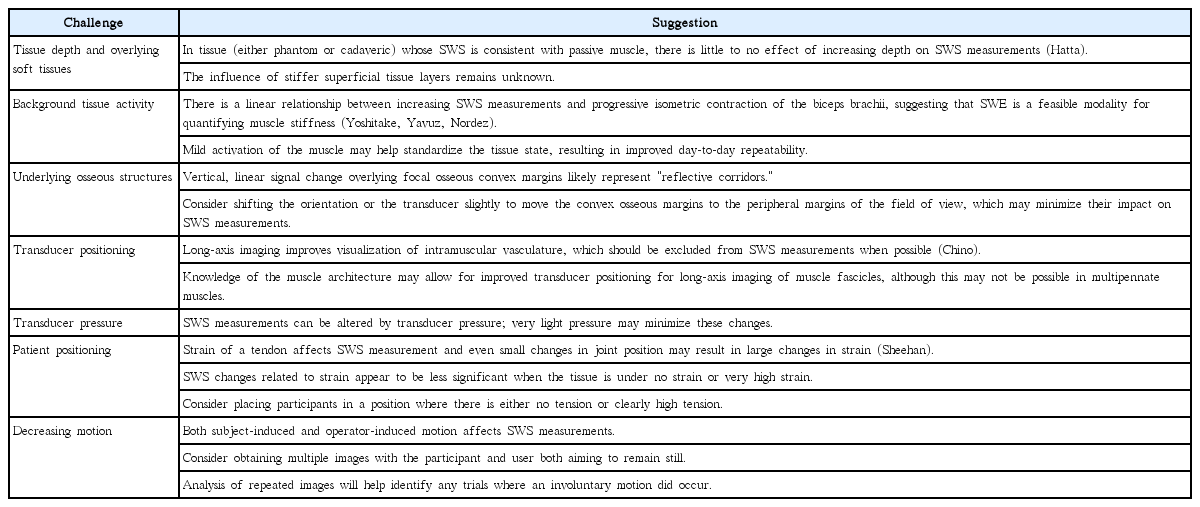

SWE, while promising in theory, requires further advances in technology and a better understanding of image acquisition before it can reliably be used for musculoskeletal imaging. The musculoskeletal system is composed of heterogeneous, anisotropic tissue, including muscles as well as complex muscle-tendonenthesis-bone interfaces that make the implementation of SWE challenging. Many of the stumbling blocks encountered during musculoskeletal SWE imaging are readily recognizable and can be overcome or minimized (Table 3); however, the effects of some obstacles on qualitative results are still not fully understood, despite ongoing research.

Summary of challenges encountered in SWE imaging of the musculoskeletal system, with suggestions for avoiding or minimizing each challenge

Continued collaboration between researchers and clinicians may enable the development of standardized imaging protocols and positions and may elucidate the causes of (and solutions for) imaging artifacts. Additionally, advancements in SWE transducer technology and more widespread distribution of SWE-capable machines may allow for a wider range of data acquisition.

Notes

Siemens Healthcare provides Marnix van Holsbeeck with ultrasound equipment. All other authors have no competing interests.